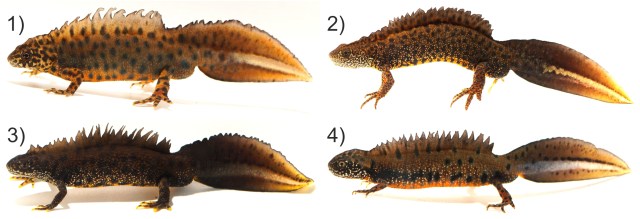

Crested newts comprise four ‘morphotypes’: 1) the Triturus karelinii-group, 2) T. carnifex + T. macedonicus, 3) T. cristatus, and 4) T. dobrogicus. These four morphotypes range from sturdy to slender bodies. Body build is reflected by the number of rib-bearing pre-sacral vertebrae (NRBV), running from NRBV=13 (most sturdy) to NRBV=16 (most slender). Hence, NRBV approximates body build in crested newts. A final fun fact is that crested newt morphotypes differ ecologically. Body build is related to the duration of the annual aquatic period, which runs from three months for NRBV=13 to six months for NRBV=16. This suggest that ecology might have driven the crested newt radiation.

Representatives of the four crested newt morphotypes, ordered from sturdy to slender: 1) T. anatolicus – NRBV=13 – aquatic 3 months; 2) T. macedonicus – NRBV=14 – aquatic 4 months; 3) T. cristatus – NRBV=15 – aquatic 5 months; 4) T. dobrogicus – NRBV=16 – aquatic 6 months. Pictures are by Michael Fahrbach.

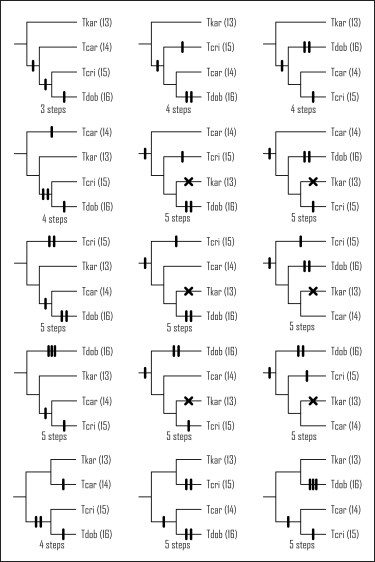

To understand how this radiation of body shapes originated in crested newts, we should look at their evolutionary tree (their phylogeny). However, despite several previous attempts, employing a variety of molecular markers, phylogenetic relationships among crested newt morphotypes have never been resolved. For four morphotypes, 15 topologies are possible. The number of additions or subtractions of rib-bearing vertebrae during crested newt evolution differs between these topologies. So how flexible was NRBV during crested newt evolution?

All possible topologies for a phylogeny for four crested newt morphotypes. The four letter abbreviations refer to the morphotypes and the NRBV value for each is between parentheses. The upper left topology requires the least amount of evolutionary change to explain the radiation in NRBV observed today.

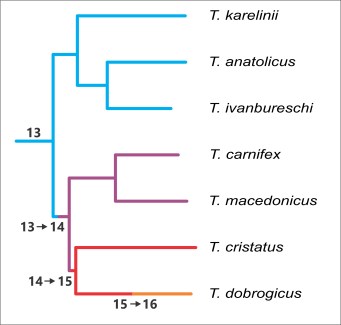

In a paper in BMC Evolutionary Biology we finally manage to obtain a well-supported, fully resolved crested newt phylogeny, by using complete mitochondrial genome sequences. We can now look at the evolution of the radiation in body build in crested newts, in the context of the new phylogeny. By taking a step back and looking at NRBV values in other salamanders, we can give NRBV evolution a direction. Most salamanders have a relatively low NRBV=13. Therefore, the root of the crested newt tree, furthest back in time, can be set at NRBV=13 as well. This means that the proto crested newt likely had a low NRBV value, like the T. karelinii-group today (which is also 13), while the higher NRBV values seen in crested newts probably evolved at a later stage.

The crested newt phylogeny based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences. The colours reflect the NRBV values of the four crested newt morphotypes. The changes in NRBV over the course of the evolution of the crested newts are noted along the branches of the tree.

A basal dichotomy separates the T. karelinii-group (NRBV=13) from the remaining crested newts. The next split divides T. carnifex + T. macedonicus (NRBV=14) versus the rest. Finally there is a divide between T. cristatus (NRBV=15) and T. dobrogicus (NRBV=16). To explain the evolution of NRBV, given the new phylogeny, three additions of a rib-bearing vertebrae are required. This actually is the minimal number of steps possible to explain the variation in NRBV observed today (in technical terms, the new phylogeny supports a maximally parsimonious interpretation of NRBV evolution). The new phylogeny makes sense!

Reference: Wielstra, B., Arntzen, J.W. (2011). Unraveling the rapid radiation of crested newts (Triturus cristatus superspecies) using complete mitogenomic sequences. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 162.

Pingback: Mitochondrial mess-up | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Trying to crack the crested newt phylogeny – and failing | Ben Wielstra