You can only learn so much about a study system if you have few genetic markers available. Particularly if that study system has an extensive history of hybridization, as is the case for Triturus. Because salamanders have massive and complex genomes it is not possible to simply sequence one. Not yet at least. Luckily we had some Triturus transcriptome data laying around. The transcriptome contains messenger DNA – the transcripts of functional genes – but not the long introns and endless repeats that torment salamander genomes. Hence it provides relatively simple, genome-wide reference data for marker design. After designing a large set of markers, I tested which of these worked for all crested newt species and multiplexed the successful ones for a large set of newts. Next the whole bunch was sequenced at Naturalis’ next-generation sequencing facility on an Ion Torrent machine and subsequently the huge amount of genetic data was sorted out with a bioinformatics pipeline and converted it to a workable format. It sounds easy, but it was quite an undertaking.

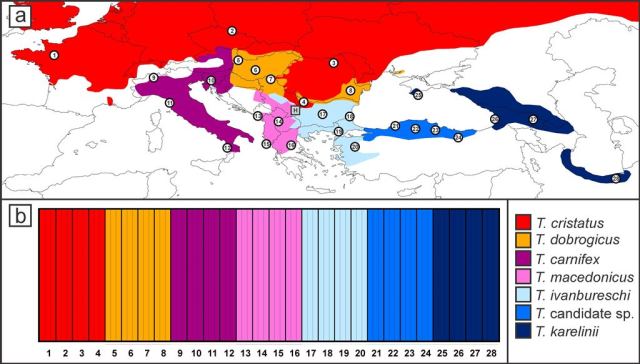

The top picture shows the localities sampled (circled numbers, three newts each) and the bottom picture shows the probability with which they belong to their own species (all 1, as would be expected if our method works).

Using data for a set of newts representing all species and also some putative hybrids we showed that the protocol can be used to allocate individuals to the proper species and pick out genetically admixed newts. Although the amount of markers is still relatively modest, the data provide a very detailed picture on the genetic composition of crested newts. A paper describing the methodology has recently been published in Molecular Ecology Resources. Basically we can now provide a detailed picture of the distribution of the different species and the genetic distinction of and gene flow between these species: an important next step in my research. Meanwhile I have sequenced about 1500 individuals throughout the range of Triturus as the basis for quite some papers to come. Stay tuned!

These are a couple of newts from the population marked with an H on the map above. You can click on the picture to see a larger version. The throat and belly pattern is very variable in this populations. Some animals look more like macedonicus or ivanbureschi and the ones depicted here look especially messy. Based on the Ion Torrent data these newts indeed show mixed macedonicus and ivanbureschi genetic ancestry and almost all are identified as backcrosses towards ivanbureschi (with the remainder being F2 hybrids).

By the way, many thanks to Wieslaw Babik, Michał Stuglik and Piotr Zieliński from Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland for helping with the design of this protocol!

Reference: Wielstra, B., Duijm, E., Lagler, P., Lammers, Y., Meilink, W., Ziermann, J.M., Arntzen, J.W. (2014). Parallel tagged amplicon sequencing of transcriptome-based genetic markers for Triturus newts with the Ion Torrent next-generation sequencing platform. Molecular Ecology Resources 14(5): 1080-1089.

Pingback: The final nail in the coffin of Triturus arntzeni | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Ribs ‘n’ genes: Triturus hybrid zones | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Mapping the European Triturus species | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Trying to crack the crested newt phylogeny – and failing | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: No subspecies for the Danube crested newt | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: The Anatolian crested newt: a new species endemic to Turkey | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Detecting alien newt alleles | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Genetic pollution in Dutch crested newts | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: A genomic footprint of hybrid zone movement in crested newts | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Refining the range dynamics of the Italian crested newt | Wielstra Lab

Pingback: Movement of the marbled newt hybrid zone | Wielstra Lab

Pingback: More resolution for the beautiful banded newts | Wielstra Lab