Where recently diverged species meet in nature, they often hybridize and exchange genes. The regions where this genetic intermingling occurs are called hybrid zones. If one member of a hybridizing pair of species displaces the other, their hybrid zone would in consequence move. For hybrid zones studied over decades, little shifts have occasionally been observed ‘live’. Of course a decade is next to nothing on an evolutionary time scale and over thousands of years a hybrid zone could potentially travel a considerable distance. Yet, theory predicts that moving hybrid zones quickly stabilize at barriers of less suitable habitat (so-called density troughs). So what’s the deal?

A male crested newt from a hybrid pond.

A male crested newt from a hybrid pond.

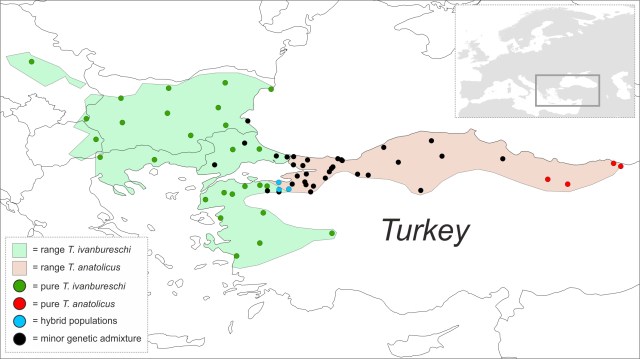

A key prediction of hybrid zone movement is that selectively neutral genes of the displaced species introgress into the expanding one en masse, while gene flow in the opposite direction is negligible. In effect the receding species leaves behind a trail of genes within the advancing species. Such a ‘genomic footprint’ of hybrid zone movement could be uncovered by screening dozens of genes. To conduct this test of long-term movement, we had better study a hybrid zone for which a shift in position is likely to begin with. Triturus provides: we previously hypothesized that in Turkey the recently recognized T. anatolicus has been expanding at the expense of T. ivanbureschi, as their hybrid zone moved to the west. Using the Ion Torrent protocol we sampled a lot of newts from many localities throughout the range of both species.

The ranges of the two crested newt species are shown green and red. Pure green or red dots are populations where animals are genetically pure and the blue dots are hybrid populations (with genes of both species at high frequency). Black dots represent populations of one species where genetic traces of the other are present. Black dots are much wider distributed in the red than in the green species.

The ranges of the two crested newt species are shown green and red. Pure green or red dots are populations where animals are genetically pure and the blue dots are hybrid populations (with genes of both species at high frequency). Black dots represent populations of one species where genetic traces of the other are present. Black dots are much wider distributed in the red than in the green species.

In a paper just published in the new journal Evolution Letters, we show that introgression between the two crested newt species is strongly biased. As predicted, we find considerably more genes of T. ivanbureschi in T. anatolicus then the reverse. This asymmetric introgression spans an extensive area. Our findings provide powerful evidence for a scenario in which T. anatolicus has been displacing T. ivanbureschi, while the two hybridized in the process. Theory be damned, the crested newt case strongly suggests that hybrid zone movement can proceed over considerable time and space! Hybrid zones are probably much more mobile than currently appreciated.

When plotting the fraction of genetic material derived from each species (ancestry) vs. the fraction of genes that posses a copy of either species (heterozygosity), a pure ‘green species’ would turn up in the lower left and a pure ‘red species’ in the lower right corner, while an F1 hybrid between the two species would end up in the upper corner. Plotted individuals are more widely spread in the lower right than in the lower left corner. This means that there are much more red individuals that possess some green genes, rather than the other way around.

When plotting the fraction of genetic material derived from each species (ancestry) vs. the fraction of genes that posses a copy of either species (heterozygosity), a pure ‘green species’ would turn up in the lower left and a pure ‘red species’ in the lower right corner, while an F1 hybrid between the two species would end up in the upper corner. Plotted individuals are more widely spread in the lower right than in the lower left corner. This means that there are much more red individuals that possess some green genes, rather than the other way around.

Reference: Wielstra, B., Burke, T., Butlin, R.K., Avcıc, A., Üzüm, N., Bozkurt, E., Olgun, K., Arntzen, J.W. (2017). A genomic footprint of hybrid zone movement in crested newts. Evolution Letters 1 (2): 93-101.

Reference: Wielstra, B., Arntzen, P. (2018). Schuivende hybridezones in kamsalamanders: hybridezones blijken beweeglijker dan gedacht. RAVON 20(4): 64-67.

Congratulations! Very nice article! And thank god not paywalled.

Will the same sort of research be useful for T. cristatus and T. marmoratus in France for example? Just to see if either species has left some fixed genetic footprints inside the other?

One question however:

“Western alleles are found in the

eastern species in a much more extensive area (localities 39, 43,

and 47–63 in Fig. 1A) than the reverse (localities 12, 16, 17, 30,

and 34), reaching up to c. 600 km east and c. 200 km west of the

hybrid zone.”

Take for example locality 47. The individuals contain Western MtDNA and introgressed Western nuclear alleles. How do you determine that these individuals still belong to T. anatolicus and not to T. ivanbureschi with introgressed eastern alleles?

Thanks. Because hybrids between crested and marbled newts have a very low fitness gene flow must be much rarer and therefore I would suspect a larger number of markers are required to test for it. In the current paper species identity is based on the overall genetic composition, reflected by the Structure score. So for locality 47 the minimum score for any of the individuals to belong to the eastern species is 0.991.

Pingback: A crested newt enclave predicts species replacement | Ben Wielstra

Pingback: Is historical hybrid zone movement underappreciated? | Wielstra Lab

Pingback: Movement of the marbled newt hybrid zone | Wielstra Lab

Pingback: More resolution for the beautiful banded newts | Wielstra Lab

Pingback: Delineating a crested newt hybrid zone with DNA data | Wielstra Lab