It is quite easy to tell apart males and females of the smooth newt species complex (Lissotriton vulgaris and related species) when observing adults in ponds during the breeding season. They clearly differ by their secondary sexual characteristics: males are splendidly colored and sport a crest, while females are more drab. But what about animals outside the breeding season – or juveniles, larvae and embryos? To sex these you would need to resort to genetic methods. However, this is not straightforward: while newts have huge genomes, their sex-chromosomes are hardly diverged.

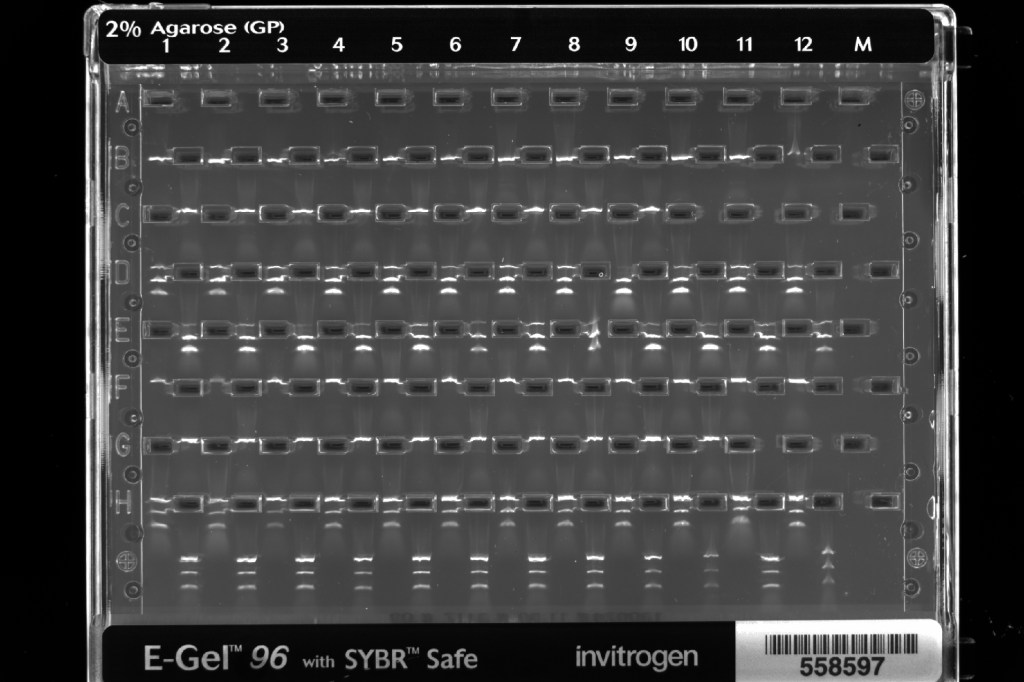

In the first paper resulting from his PhD thesis, out in Molecular Ecology Resources, my student James France undertook a massive study to design sex markers for the smooth newts. He compared two distinct ways of design: 1) looking at consistent differences in random DNA obtained from a sizable sample of males and females; and 2) looking at the distribution of DNA differences that are only present in the offspring of, in this case, the father (because in smooth newts the males have an X and a Y version of the sex chromosome). To cut a long story short: the conclusion of James’ study is that the first method works best. Based on the data collected, he designed a genetic tool that allows any member of the smooth newt species complex to be sexed. James’ approach to genetically sex salamanders should be broadly applicable.

Reference: France, J., Babik, W., Dudek, K., Marszałek, M., Wielstra, B. (2025). Linkage mapping vs Association: A comparison of two RADseq-based approaches to identify markers for homomorphic sex chromosomes in large genomes. Molecular Ecology Resources 25(7): e70019.

Pingback: No support for a link between the balanced lethal system and ancient sex chromosomes | Wielstra Lab