A beautiful banded newt because why not (Michael Fahrbach)

A follow-up study on the evolution of the immune system in salamanders, again led by Gemma Palomar and Wiesław Babik, is just out in Molecular Biology and Evolution. We conduct an analysis, recommended in our previous collaboration, in which we test if the diversity of two important players in the immune system, namely the major histocompatibility complex class I and the antigen-processing genes, is correlated across the salamander tree of life. Such correlation is expected if the two coevolve. Coevolution could make the salamander immune response more effective, but would come at the cost of its flexibility. Analysis of an enormous genetic dataset indeed supports co-evolution in the salamander immune system. However, this co-evolution also coincides with extensive duplication of major histocompatibility complex class I genes, increasing flexibility in dealing with new pathogens. Therefore, the salamander immune response reflects a best of both worlds situation.

Reference: Palomar, G., Dudek, K., Migalska, M., Arntzen, J.W., Ficetola, G.F., Jelić, D., Jockusch, E., Martínez-Solano, I., Matsunami, M., Shaffer, H.B., Vörös, J., Waldman, B., Wielstra, B., Babik, W. (2021). Coevolution between MHC class I and Antigen Processing Genes in salamanders. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38(11): 5092-5106.

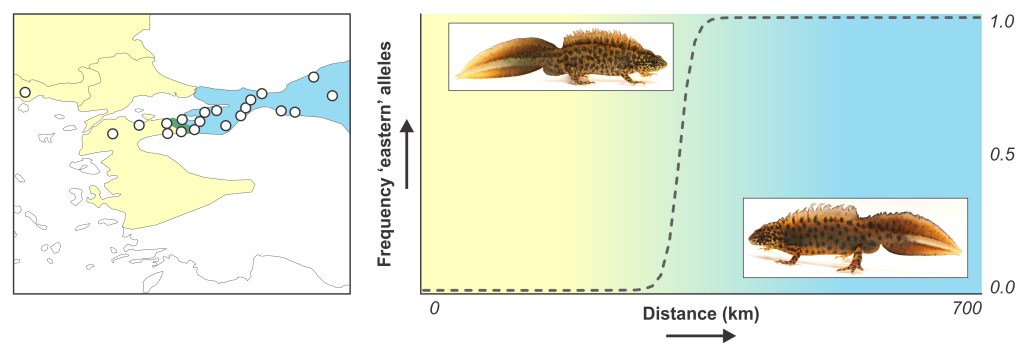

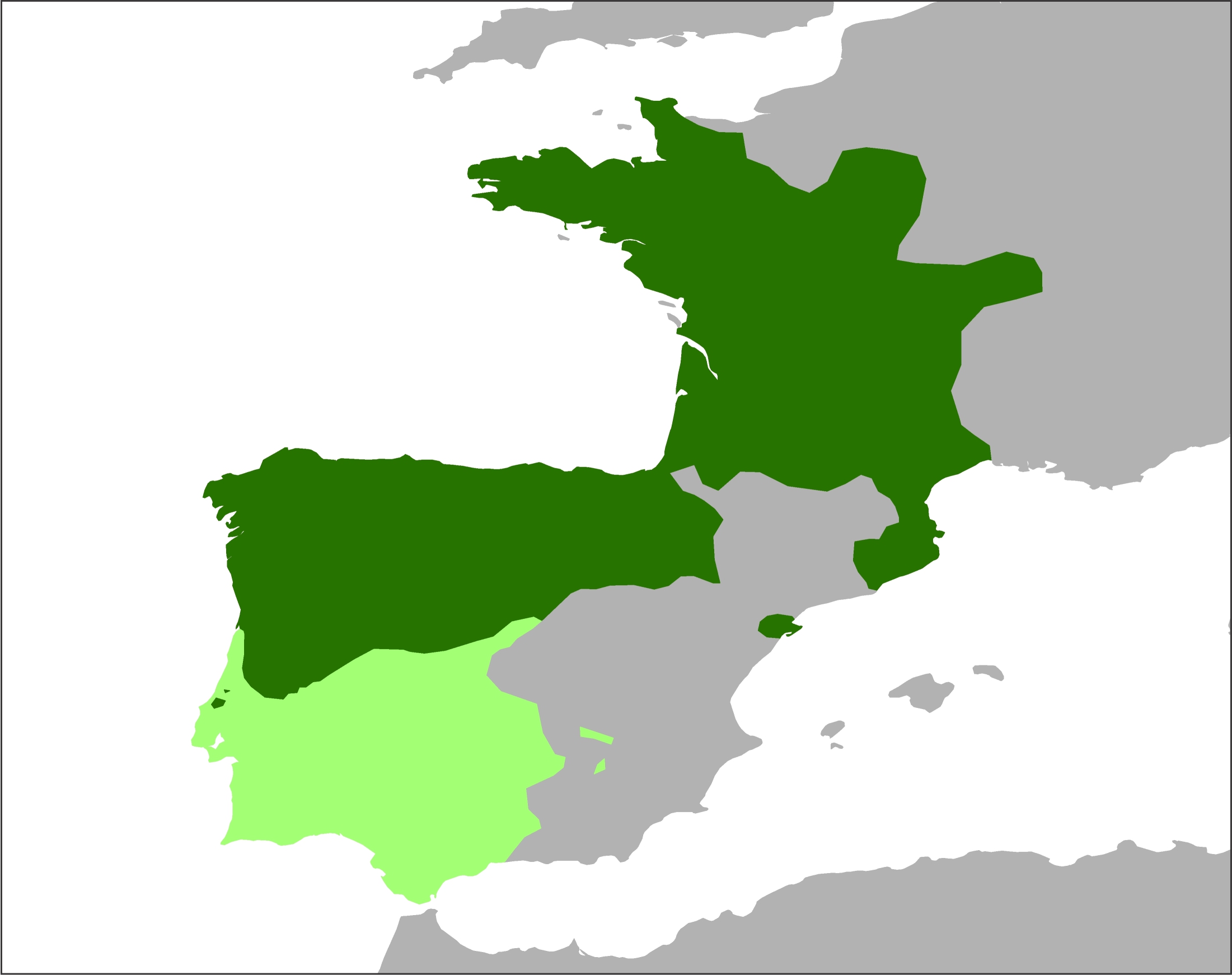

The hybrid zone between the pygmy marbled newt (light) and marbled newt (dark) is hypothesized to move northwards, based on marbled newt distribution relics left in the wake of the hybrid zone.

The hybrid zone between the pygmy marbled newt (light) and marbled newt (dark) is hypothesized to move northwards, based on marbled newt distribution relics left in the wake of the hybrid zone.

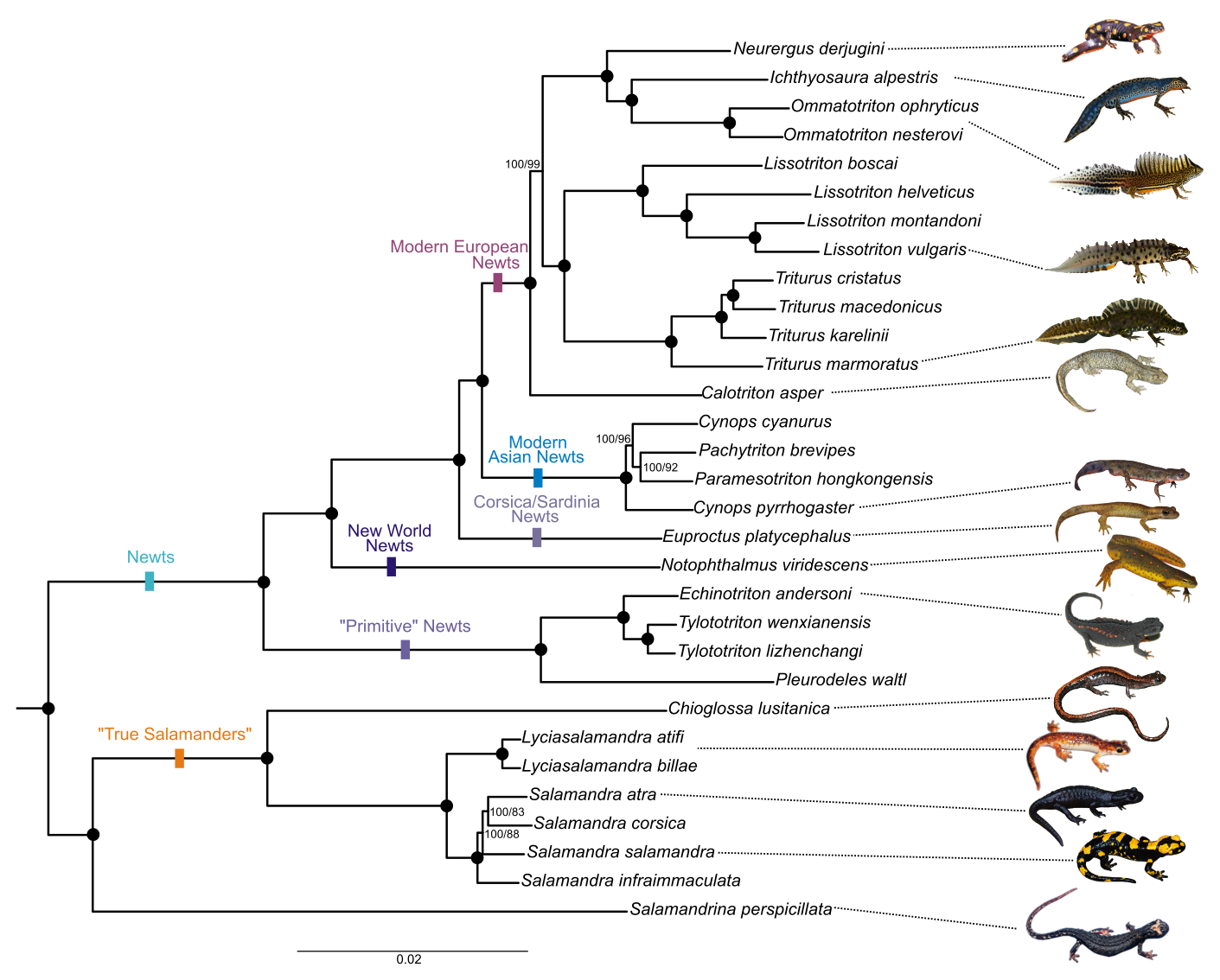

Reference: Rancilhac, L., Irisarri, I., Angelini, C., Arntzen, J.W., Babik, W., Bossuyt, F., M., Künzel, S., Lüddecke, T., Pasmans, F., Sanchez, E., Weisrock, D., Veith, M., Wielstra, B., Steinfartz, S., Hofreiter, M., Philippe, H., Vences, M. (2021). Phylotranscriptomic evidence for pervasive ancient hybridization among Old World salamanders.

Reference: Rancilhac, L., Irisarri, I., Angelini, C., Arntzen, J.W., Babik, W., Bossuyt, F., M., Künzel, S., Lüddecke, T., Pasmans, F., Sanchez, E., Weisrock, D., Veith, M., Wielstra, B., Steinfartz, S., Hofreiter, M., Philippe, H., Vences, M. (2021). Phylotranscriptomic evidence for pervasive ancient hybridization among Old World salamanders.