Invasive species threaten native biota, not only through competition, predation and infection, but also via hybridization. Human-induced hybridization has important implications from the point of view of conservation as it results in genetic replacement – a loss of biodiversity at the level of the gene. However, because hybridizing species are often closely related and morphologically similar, ‘genetic pollution’ is insidious. To expose and quantify genetic pollution, genetic data need to be consulted.

In several localities within the range of the threatened Northern crested newt (Triturus cristatus), the Italian crested newt (T. carnifex) has been introduced. In the Netherlands T. carnifex has established itself on the Veluwe and poses a potential threat there to the native T. cristatus. At the request of the Invasive Alien Species Team, my MSc. student Willem Meilink and I, in collaboration with the Dutch NGO RAVON (Reptile, Amphibian and Fish Conservation Netherlands), used the new Triturus Ion Torrent protocol to explore the issue of genetic pollution of T. cristatus by T. carnifex. We recently published a paper in Biological Conservation on the case. Populations vary from completely invasive, via different degrees of genetic admixture, to completely native, when sampling outwards from the initial site of introduction of the exotic species. The observed pattern shows that the two crested newt species are hybridizing on the Veluwe and that the exotic T. carnifex is expanding at the expense of the native T. cristatus.

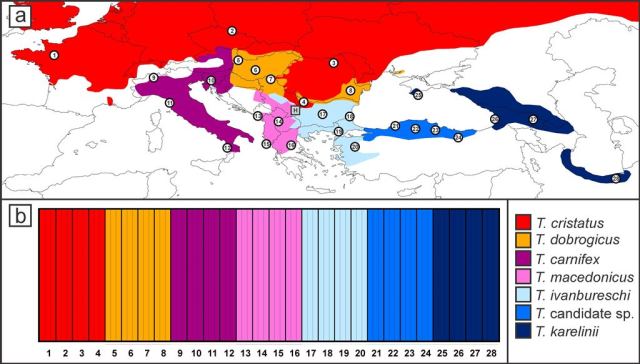

This figure shows the study area with eleven studied ponds (above) and the genetic composition of twelve individuals sampled for each pond (below). From pond 1 to 11 the proportion of genetic material of the invasive T. carnifex (blue) decreases, whereas that of the native, threatened T. cristatus (red) increases. The top panel also shows the distribution of mitochondrial DNA in the ponds (using the same color scheme); note that it underestimates the spread of T. carnifex.

Our study shows that the invasive species poses a threat to the native species through genetic pollution. However, countering this threat, if one would decide to do so, is far from straightforward. Which individuals deserve protection? How to deal with individuals with an almost native genotype? What is the legal status of such individuals? Even when you have made a decision, how will you establish in practice whether a particular individual meets your requirement? Are there instances where you should consider maintaining genetic integrity of the native species infeasible? What if most individuals have become polluted? Tackling these dilemmas requires interaction between scientists, conservationists, legislators and land managers. We hope this case study will help drafting as yet non-existent guidelines for the management of genetic pollution.

This study was funded by the Invasive Alien Species Team, which advices the Ministry of Economic Affairs on the management of invasive species, and it was conducted in collaboration with the Dutch NGO RAVON (Reptile, Amphibian and Fish Conservation Netherlands), responsible for monitoring amphibians (and reptiles and fish) in the Netherlands.

Reference: Meilink, W.R.M., Arntzen, J.W., van Delft, J.C.W., Wielstra, B. (2015) Genetic contamination of a native threatened crested newt species through hybridization with an invasive congener. Biological Conservation 184: 145-153.

Reference: Wielstra, B., Arntzen, P., van Delft, J., Meilink, W. (2015). Genetische vervuiling op de Veluwe: hybridisatie tussen een inheemse en een exotische kamsalamandersoort. RAVON 17(2): 36-39.

Reference: Meilink, W.R.M., Arntzen, J.W., Wielstra, B. (2013). Genetische vervuiling op de Veluwe: Hybridisatie tussen de inheemse Noordelijke kamsalamander en de invasieve exoot Italiaanse kamsalamander. Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden.

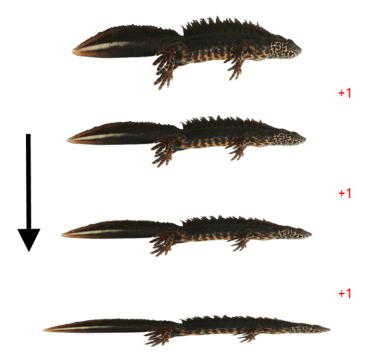

From top to bottom these are a normal adult male, a paedomorphic male, a paedomorphic female and a normal adult female Kosswig’s newt. Notice the gills of the paedomorphs. The male shows a swollen cloaca, meaning it is sexually mature and hence an adult.

From top to bottom these are a normal adult male, a paedomorphic male, a paedomorphic female and a normal adult female Kosswig’s newt. Notice the gills of the paedomorphs. The male shows a swollen cloaca, meaning it is sexually mature and hence an adult. The Kosswig’s (top) and Schmidtler’s newt are quite different. The crest is smooth and starts above the forelimbs in the Kosswig’s newt and is ragged and starts in the neck in Schmidtler’s newt. The Kosswig’s also differs from the Schmidtler’s newt in having a threadlike tail filament and very flappy feet.

The Kosswig’s (top) and Schmidtler’s newt are quite different. The crest is smooth and starts above the forelimbs in the Kosswig’s newt and is ragged and starts in the neck in Schmidtler’s newt. The Kosswig’s also differs from the Schmidtler’s newt in having a threadlike tail filament and very flappy feet.