The Quaternary Ice Age heavily influenced the distribution of species. During the colder glacial periods, species went extinct in part of their range, while during warmer interglacial periods, they could recolonize these regions again. This contraction-expansion pattern left its mark on genetic diversity across species’ ranges, with high diversity in regions where species survived continuously, and low diversity in regions where they were periodically wiped out. Past range shifts can also be visualized by projecting species distribution models, based on the environmental conditions currently experienced, on climate reconstructions of the past.

In a study published in Frontiers in Zoology we explore how all the marbled and crested newts species (so the entire genus Triturus) responded to the climate change associated with the Ice Age. We conduct a phylogeographical survey, meaning we sequence a lot of mitochondrial DNA, for many populations throughout each of the species ranges, and look at variation in genetic diversity across species ranges. Additionally, we compare species distribution models projected on current and on past climate layers (the Last Glacial Maximum, about 21,000 years ago).

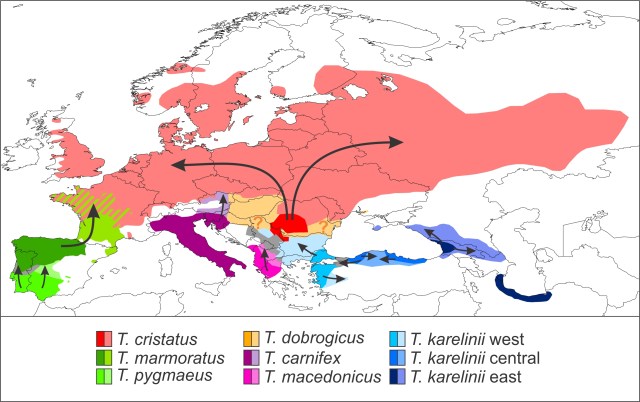

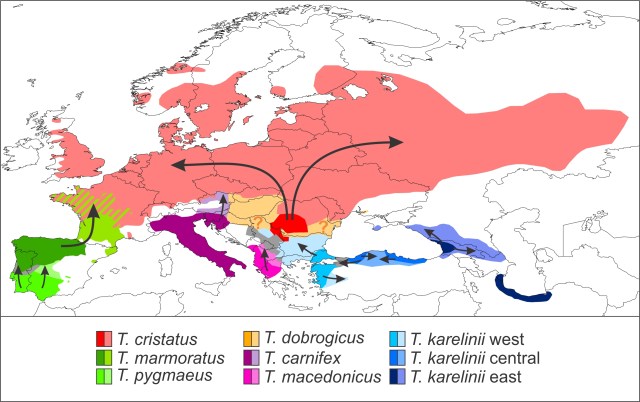

A visualization of the biogeographical scenario proposed, showing the positions of glacial refugia in dark shades and the regions postglacially colonized in light shades for each individual species. In grey areas we infer that one species displaced another as they shifted their ranges.

By combining the two independent techniques of phylogeography and species distribution modelling, we obtain a more complete understanding of the historical biogeography of the crested and marbled newts than both approaches would have provided on their own.

Reference: Wielstra, B., Crnobrnja-Isailović, J., Litvinchuk, S.N., Reijnen, B., Skidmore, A.K., Sotiropoulos, K., Toxopeus, A.G., Tzankov, N., Vukov, T., Arntzen, J.W. (2013). Tracing glacial refugia of Triturus newts based on mitochondrial DNA phylogeography and species distribution modeling. Frontiers in Zoology 10: 13.

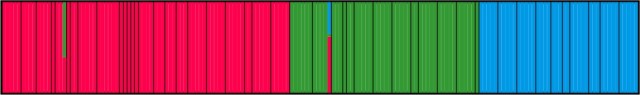

This plot shows individuals (thin bars) within populations (thick bars) roughly ordered from west to east. Based on their genotype, individuals are allocated (0-100%) to three geographical genetic groups (represented by different colors).

This plot shows individuals (thin bars) within populations (thick bars) roughly ordered from west to east. Based on their genotype, individuals are allocated (0-100%) to three geographical genetic groups (represented by different colors). Here you see the three cryptic species that make up the T. karelinii-group of crested newts. An intriguing finding is that asymmetric DNA introgression from the western group into the central group (the red-green hatched area). We suggest that this pattern can be explained by the central group having expanded its range at the expense of the western group, while the two hybridized in the process. An interesting hypothesis to test in a future study!

Here you see the three cryptic species that make up the T. karelinii-group of crested newts. An intriguing finding is that asymmetric DNA introgression from the western group into the central group (the red-green hatched area). We suggest that this pattern can be explained by the central group having expanded its range at the expense of the western group, while the two hybridized in the process. An interesting hypothesis to test in a future study!

This figure shows how mitochondrial DNA can be transferred across the species boundary via introgressive hybridization. Large circles reflect the nuclear DNA composition of individuals and small ones their mitochondrial DNA type. There is an initial hybridization event between the members of two species, a red female and a green male. The F1 offspring contain a mix of red and green nuclear DNA, as this is inherited from both parents, but only red mitochondrial DNA, because mitochondrial DNA is only transmitted via the mother. Over subsequent generations, admixed females mate (backcross) with green males. In time the red nuclear DNA dilutes out and in effect we end up with a species that, from the nuclear DNA perspective, is completely green, but that possesses red mitochondrial DNA.

This figure shows how mitochondrial DNA can be transferred across the species boundary via introgressive hybridization. Large circles reflect the nuclear DNA composition of individuals and small ones their mitochondrial DNA type. There is an initial hybridization event between the members of two species, a red female and a green male. The F1 offspring contain a mix of red and green nuclear DNA, as this is inherited from both parents, but only red mitochondrial DNA, because mitochondrial DNA is only transmitted via the mother. Over subsequent generations, admixed females mate (backcross) with green males. In time the red nuclear DNA dilutes out and in effect we end up with a species that, from the nuclear DNA perspective, is completely green, but that possesses red mitochondrial DNA. This figure shows two scenarios that could result in geographically asymmetric mitochondrial DNA introgression. We have a green and a red species. The background reflects nuclear DNA composition in space. Circles reflect the spatial distribution of mitochondrial DNA. The black bar represents the hybrid zone between the two species and the grey boundary the geographical overturn between the two mitochondrial DNA types. In both panels mitochondrial DNA of the red species has introgressed into the green one when they started hybridizing. In the top panel the green species subsequently outcompetes the red one and the species boundary moves towards the left. The green individuals at the frontier possess red mitochondrial DNA, and so does their offspring that gradually replaces the red species. Therefore, red but not green mitochondrial DNA is spread into the region of species replacement via the green species (where red mitochondrial DNA is already present in the red species). Hence, the location of the geographical overturn between the two mitochondrial DNA types remains the same. In the bottom panel the location of the hybrid zone between the green and the red species is stable. However, the red mitochondrial DNA is beneficial to the green species and natural selection pulls it further and further into the green range over time. In effect, the geographical overturn between the two mitochondrial DNA types moves towards the left.

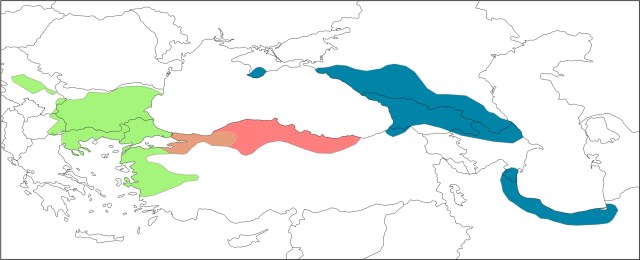

This figure shows two scenarios that could result in geographically asymmetric mitochondrial DNA introgression. We have a green and a red species. The background reflects nuclear DNA composition in space. Circles reflect the spatial distribution of mitochondrial DNA. The black bar represents the hybrid zone between the two species and the grey boundary the geographical overturn between the two mitochondrial DNA types. In both panels mitochondrial DNA of the red species has introgressed into the green one when they started hybridizing. In the top panel the green species subsequently outcompetes the red one and the species boundary moves towards the left. The green individuals at the frontier possess red mitochondrial DNA, and so does their offspring that gradually replaces the red species. Therefore, red but not green mitochondrial DNA is spread into the region of species replacement via the green species (where red mitochondrial DNA is already present in the red species). Hence, the location of the geographical overturn between the two mitochondrial DNA types remains the same. In the bottom panel the location of the hybrid zone between the green and the red species is stable. However, the red mitochondrial DNA is beneficial to the green species and natural selection pulls it further and further into the green range over time. In effect, the geographical overturn between the two mitochondrial DNA types moves towards the left. This figure shows the geographical distribution of the two crested newt species and their mitochondrial DNA as Thiessen polygons (a.k.a. a Voronoi diagram). Each polygon covers the area that is closer to its corresponding crested newt locality than to another one. Green and blue polygons represent T. macedonicus and T. ivanbureschi localities with T. macedonicus and T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA, respectively. The red polygons represent T. macedonicus localities with T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA and the orange ones T. macedonicus localities where both T. macedonicus and T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA are present. To delimit the introgression zone, we combined the orange and red polygons. The purple at the top reflects the area where other Triturus species are present, while the grey land (and white sea, obviously) is devoid of Triturus newts.

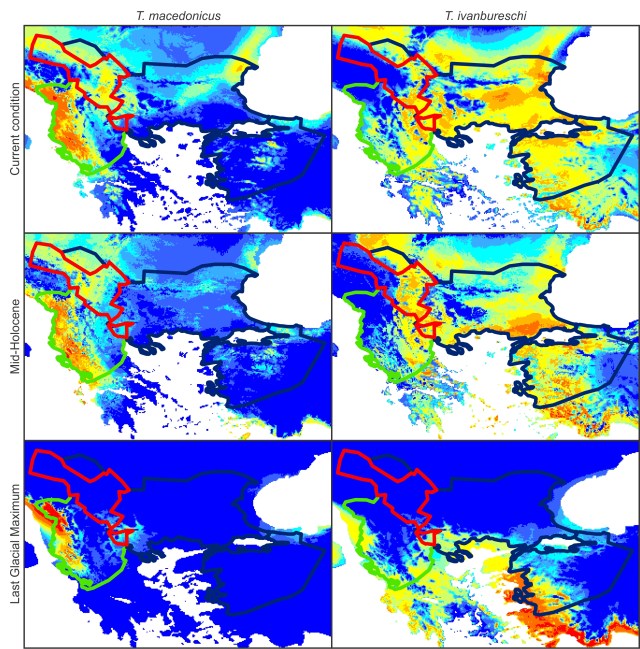

This figure shows the geographical distribution of the two crested newt species and their mitochondrial DNA as Thiessen polygons (a.k.a. a Voronoi diagram). Each polygon covers the area that is closer to its corresponding crested newt locality than to another one. Green and blue polygons represent T. macedonicus and T. ivanbureschi localities with T. macedonicus and T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA, respectively. The red polygons represent T. macedonicus localities with T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA and the orange ones T. macedonicus localities where both T. macedonicus and T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA are present. To delimit the introgression zone, we combined the orange and red polygons. The purple at the top reflects the area where other Triturus species are present, while the grey land (and white sea, obviously) is devoid of Triturus newts. This figure shows species distribution models for T. macedonicus (left) and T. ivanburschi (right) projected on climate layers for the Last Glacial Maximum (bottom), Mid-Holocene (middle) and the present (top). The warmer the color, the more suitable the area. The blue line delineates the T. ivanbureschi range (with T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA). The green line delineates the T. macedonicus range where its own mitochondrial DNA and the red line where this species carries introgressed T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA. As you can see, the introgression zone was inhospitable for either species during the Last Glacial Maximum, suggesting that the pattern we observe today was established at a later stage. However, the zone would have been habitable again at the mid-Holocene. Since that time habitat suitability generally increased for T. macedonicus, while it decreased for T. ivanbureschi.

This figure shows species distribution models for T. macedonicus (left) and T. ivanburschi (right) projected on climate layers for the Last Glacial Maximum (bottom), Mid-Holocene (middle) and the present (top). The warmer the color, the more suitable the area. The blue line delineates the T. ivanbureschi range (with T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA). The green line delineates the T. macedonicus range where its own mitochondrial DNA and the red line where this species carries introgressed T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA. As you can see, the introgression zone was inhospitable for either species during the Last Glacial Maximum, suggesting that the pattern we observe today was established at a later stage. However, the zone would have been habitable again at the mid-Holocene. Since that time habitat suitability generally increased for T. macedonicus, while it decreased for T. ivanbureschi. This figure shows a simplified historical biogeographical scenario to explain the observed mitochondrial DNA introgression between the two crested newt species. During the adverse climate conditions of the Last Glacial Maximum, the ranges of T. macedonicus (green) and T. ivanbureschi (blue) were restricted (1). When the climate improved, both species started to expand and obtained secondary contact (2). Subsequently, T. macedonicus invaded area occupied by T. ivanbureschi and locally took over, but as species displacement coincided with hybridization, T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA was left behind in this part of the T. macedonicus range (3).

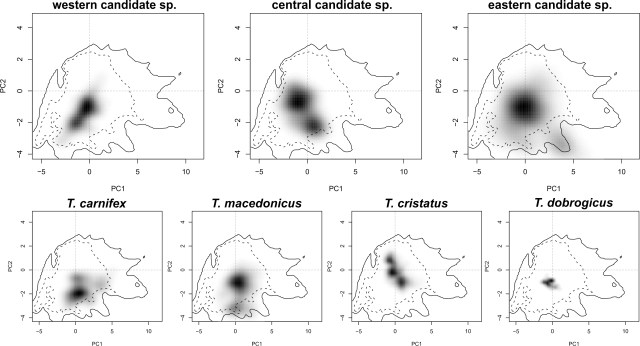

This figure shows a simplified historical biogeographical scenario to explain the observed mitochondrial DNA introgression between the two crested newt species. During the adverse climate conditions of the Last Glacial Maximum, the ranges of T. macedonicus (green) and T. ivanbureschi (blue) were restricted (1). When the climate improved, both species started to expand and obtained secondary contact (2). Subsequently, T. macedonicus invaded area occupied by T. ivanbureschi and locally took over, but as species displacement coincided with hybridization, T. ivanbureschi mitochondrial DNA was left behind in this part of the T. macedonicus range (3). In these squares you see a two dimensional representation of the niche space experienced by all crested newts together. The grey shading reflects the occurrence of each (candidate) species within that niche space.

In these squares you see a two dimensional representation of the niche space experienced by all crested newts together. The grey shading reflects the occurrence of each (candidate) species within that niche space.