Invasive species threaten native biota, not only through competition, predation and infection, but also via hybridization. Human-induced hybridization has important implications from the point of view of conservation as it results in genetic replacement – a loss of biodiversity at the level of the gene. However, because hybridizing species are often closely related and morphologically similar, ‘genetic pollution’ is insidious. To expose and quantify genetic pollution, genetic data need to be consulted.

In several localities within the range of the threatened Northern crested newt (Triturus cristatus), the Italian crested newt (T. carnifex) has been introduced. In the Netherlands T. carnifex has established itself on the Veluwe and poses a potential threat there to the native T. cristatus. At the request of the Invasive Alien Species Team, my MSc. student Willem Meilink and I, in collaboration with the Dutch NGO RAVON (Reptile, Amphibian and Fish Conservation Netherlands), used the new Triturus Ion Torrent protocol to explore the issue of genetic pollution of T. cristatus by T. carnifex. We recently published a paper in Biological Conservation on the case. Populations vary from completely invasive, via different degrees of genetic admixture, to completely native, when sampling outwards from the initial site of introduction of the exotic species. The observed pattern shows that the two crested newt species are hybridizing on the Veluwe and that the exotic T. carnifex is expanding at the expense of the native T. cristatus.

This figure shows the study area with eleven studied ponds (above) and the genetic composition of twelve individuals sampled for each pond (below). From pond 1 to 11 the proportion of genetic material of the invasive T. carnifex (blue) decreases, whereas that of the native, threatened T. cristatus (red) increases. The top panel also shows the distribution of mitochondrial DNA in the ponds (using the same color scheme); note that it underestimates the spread of T. carnifex.

Our study shows that the invasive species poses a threat to the native species through genetic pollution. However, countering this threat, if one would decide to do so, is far from straightforward. Which individuals deserve protection? How to deal with individuals with an almost native genotype? What is the legal status of such individuals? Even when you have made a decision, how will you establish in practice whether a particular individual meets your requirement? Are there instances where you should consider maintaining genetic integrity of the native species infeasible? What if most individuals have become polluted? Tackling these dilemmas requires interaction between scientists, conservationists, legislators and land managers. We hope this case study will help drafting as yet non-existent guidelines for the management of genetic pollution.

This study was funded by the Invasive Alien Species Team, which advices the Ministry of Economic Affairs on the management of invasive species, and it was conducted in collaboration with the Dutch NGO RAVON (Reptile, Amphibian and Fish Conservation Netherlands), responsible for monitoring amphibians (and reptiles and fish) in the Netherlands.

Reference: Meilink, W.R.M., Arntzen, J.W., van Delft, J.C.W., Wielstra, B. (2015) Genetic contamination of a native threatened crested newt species through hybridization with an invasive congener. Biological Conservation 184: 145-153.

Reference: Wielstra, B., Arntzen, P., van Delft, J., Meilink, W. (2015). Genetische vervuiling op de Veluwe: hybridisatie tussen een inheemse en een exotische kamsalamandersoort. RAVON 17(2): 36-39.

Reference: Meilink, W.R.M., Arntzen, J.W., Wielstra, B. (2013). Genetische vervuiling op de Veluwe: Hybridisatie tussen de inheemse Noordelijke kamsalamander en de invasieve exoot Italiaanse kamsalamander. Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden.

I conducted this work as a Newton International Fellow.

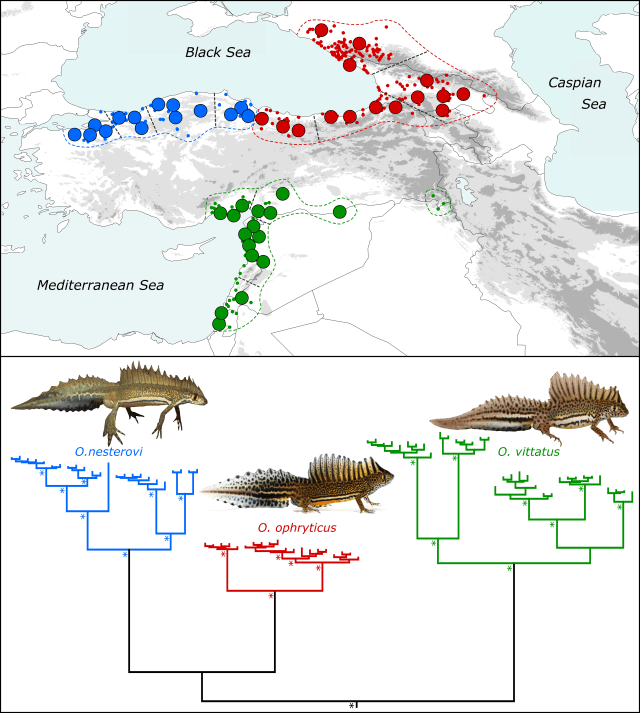

Ommatotriton nesterovi (left) and O. ophryticus.

Ommatotriton nesterovi (left) and O. ophryticus.

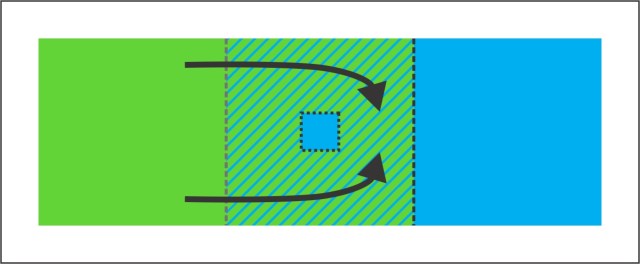

A scenario in which an enclave is created via incomplete species replacement. A green species expands to the right and replaces a blue one. However, a relict population of blue persists locally within the green range. If the two species hybridize, a genomic footprint of hybrid zone movement would be expected in the part of the green range that was formerly occupied by the blue species (on the right side of the grey dotted line).

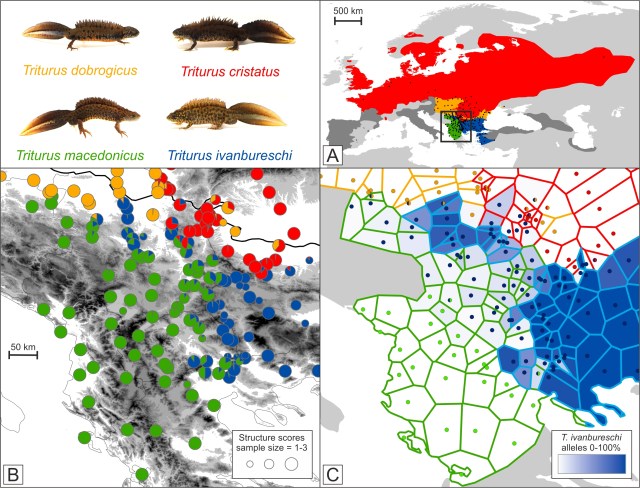

A scenario in which an enclave is created via incomplete species replacement. A green species expands to the right and replaces a blue one. However, a relict population of blue persists locally within the green range. If the two species hybridize, a genomic footprint of hybrid zone movement would be expected in the part of the green range that was formerly occupied by the blue species (on the right side of the grey dotted line). In panel A the range of the genus Triturus is shown, with approximate outlines of the ranges of the four species under study shown in color (ranges of additional Triturus species are in dark grey). Dots are sampled localities. The box delineates part of the Balkan Peninsula, highlighted in the other panels. In panel B pie diagrams illustrate the average genetic composition per locality, with pie slices colored according to species. In panel C each polygon represents a locality and includes the area that is closest to that locality, rather than another one. The border of each polygon is colored according to the genetically dominant species. The blue shading of polygons reflects the proportion of alleles that are diagnostic for the crested newt species with the enclave (T. ivanbureschi) at that locality. Finally, the dots reflect the actual position of each locality and are colored according to the type of mitochondrial DNA present. What this admittedly rather complicated picture shows is that a blue enclave (belonging to the species T. ivanbureschi) is disconnected from the main range because the range of a green species (T. macedoncius) intervenes. In the part of the range of the green species where we expect that it replaced the blue species, we find genetic traces of that blue species, just as we predicted.

In panel A the range of the genus Triturus is shown, with approximate outlines of the ranges of the four species under study shown in color (ranges of additional Triturus species are in dark grey). Dots are sampled localities. The box delineates part of the Balkan Peninsula, highlighted in the other panels. In panel B pie diagrams illustrate the average genetic composition per locality, with pie slices colored according to species. In panel C each polygon represents a locality and includes the area that is closest to that locality, rather than another one. The border of each polygon is colored according to the genetically dominant species. The blue shading of polygons reflects the proportion of alleles that are diagnostic for the crested newt species with the enclave (T. ivanbureschi) at that locality. Finally, the dots reflect the actual position of each locality and are colored according to the type of mitochondrial DNA present. What this admittedly rather complicated picture shows is that a blue enclave (belonging to the species T. ivanbureschi) is disconnected from the main range because the range of a green species (T. macedoncius) intervenes. In the part of the range of the green species where we expect that it replaced the blue species, we find genetic traces of that blue species, just as we predicted.

A male crested newt from a hybrid pond.

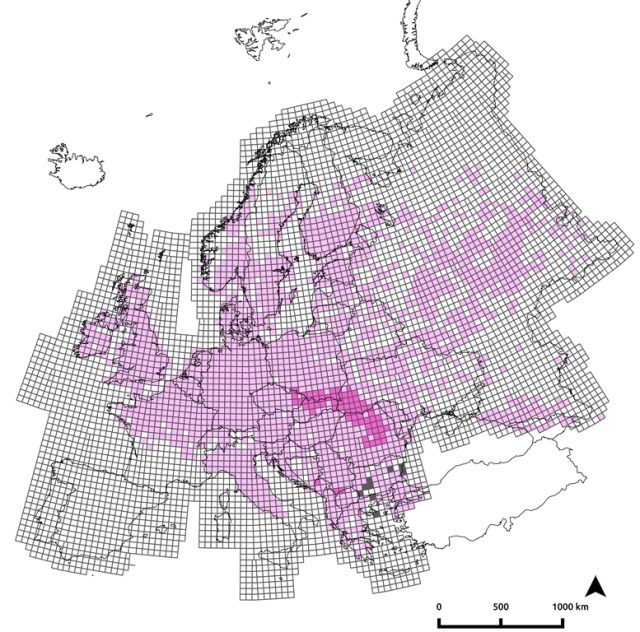

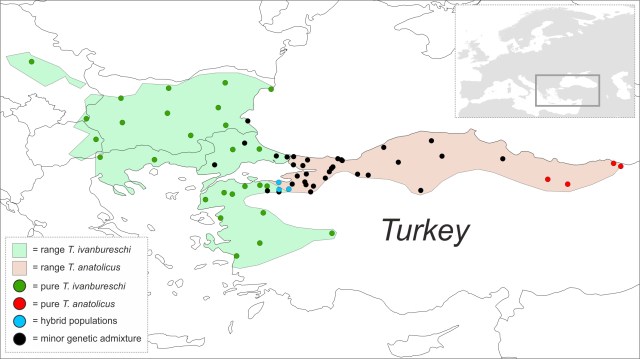

A male crested newt from a hybrid pond. The ranges of the two crested newt species are shown green and red. Pure green or red dots are populations where animals are genetically pure and the blue dots are hybrid populations (with genes of both species at high frequency). Black dots represent populations of one species where genetic traces of the other are present. Black dots are much wider distributed in the red than in the green species.

The ranges of the two crested newt species are shown green and red. Pure green or red dots are populations where animals are genetically pure and the blue dots are hybrid populations (with genes of both species at high frequency). Black dots represent populations of one species where genetic traces of the other are present. Black dots are much wider distributed in the red than in the green species. When plotting the fraction of genetic material derived from each species (ancestry) vs. the fraction of genes that posses a copy of either species (heterozygosity), a pure ‘green species’ would turn up in the lower left and a pure ‘red species’ in the lower right corner, while an F1 hybrid between the two species would end up in the upper corner. Plotted individuals are more widely spread in the lower right than in the lower left corner. This means that there are much more red individuals that possess some green genes, rather than the other way around.

When plotting the fraction of genetic material derived from each species (ancestry) vs. the fraction of genes that posses a copy of either species (heterozygosity), a pure ‘green species’ would turn up in the lower left and a pure ‘red species’ in the lower right corner, while an F1 hybrid between the two species would end up in the upper corner. Plotted individuals are more widely spread in the lower right than in the lower left corner. This means that there are much more red individuals that possess some green genes, rather than the other way around.

Male T. dobrogicus. Picture by Michael Fahrbach.

Male T. dobrogicus. Picture by Michael Fahrbach.